featured artist

Zephyr

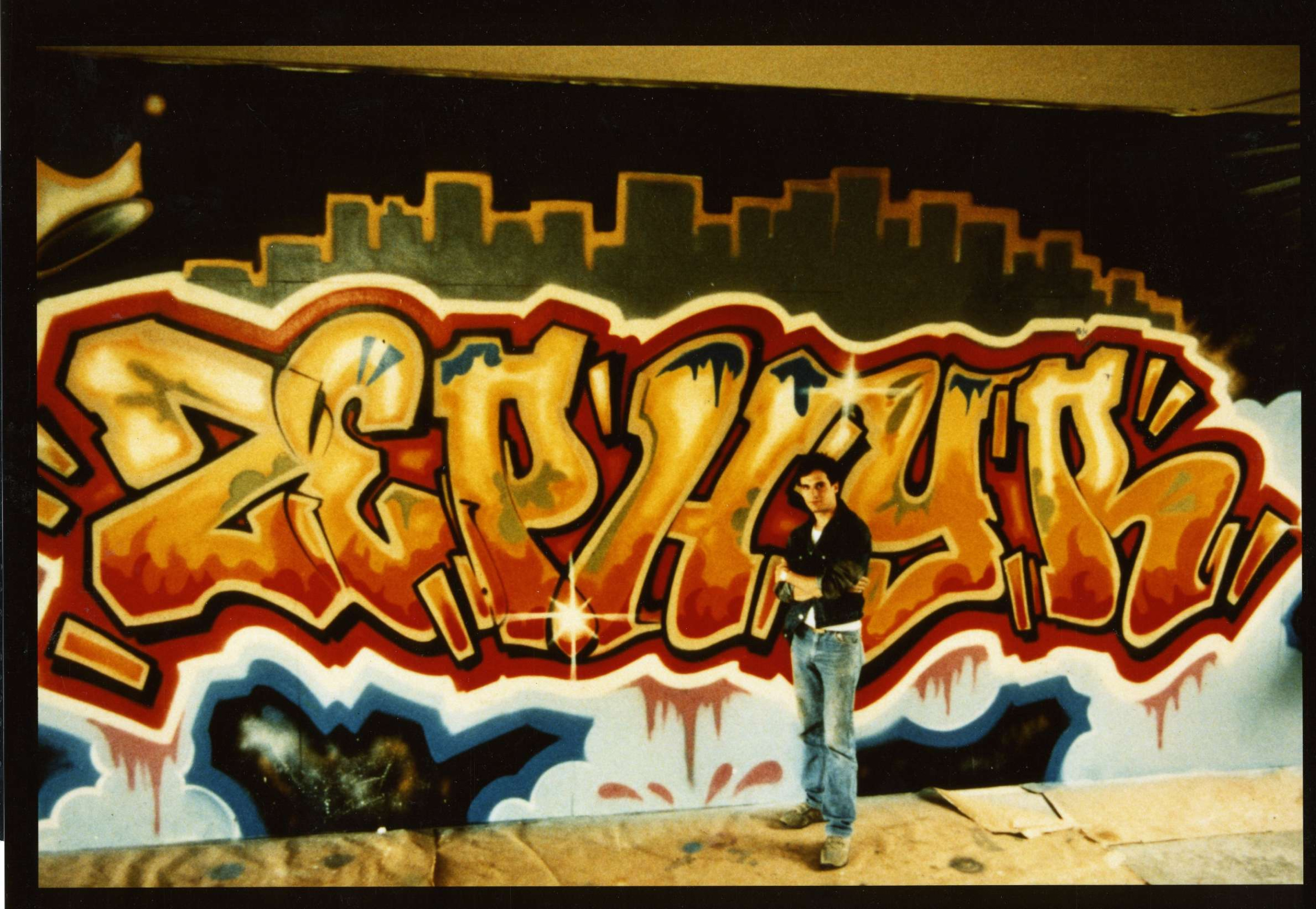

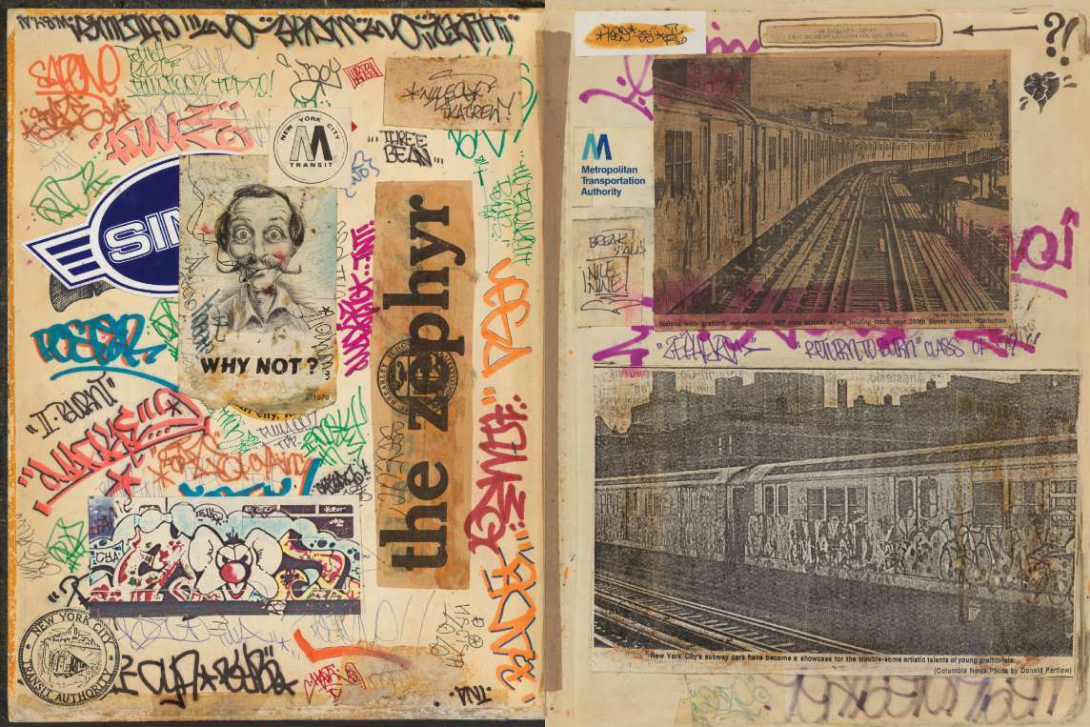

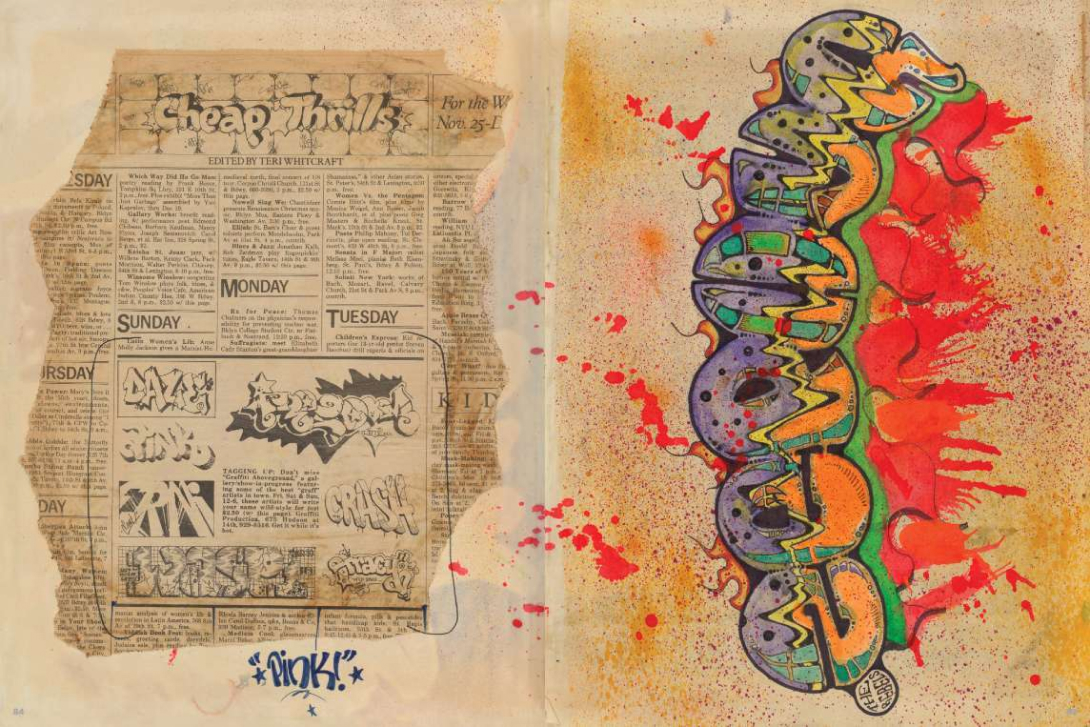

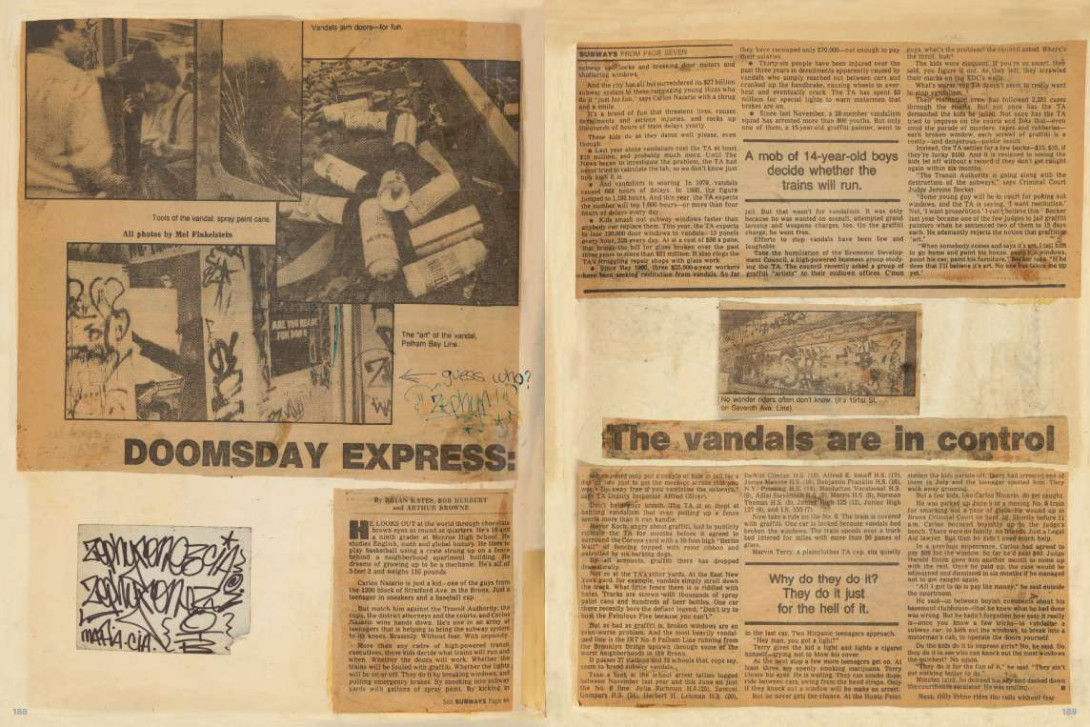

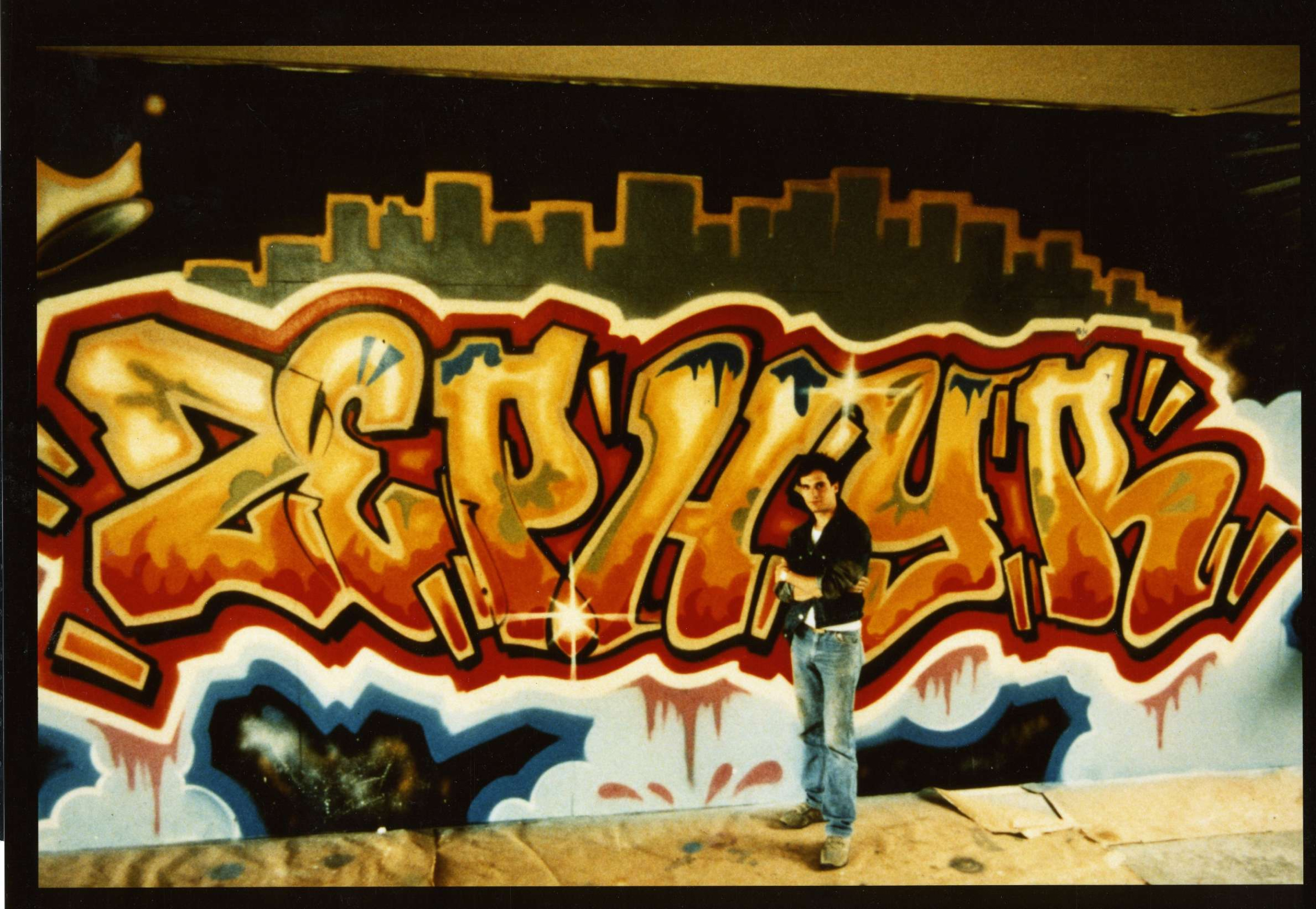

ZEPHYR (born Andrew Witten) covered New York City subway trains with his signature lettering throughout the 70s and 80s graffiti heyday, he and his work appearing in iconic movies such as Wild Style and Style Wars among others. Dubbed “the elder statesman of graffiti” by the New York Times, ZEPHYR wrote under a variety of names in the early 70s, inspired by tags he encountered in places like the transverse roads below Central Park and on the backs of bus seats. He became ZEPHYR by the winter of 1977, when he left home at the age of16—a decision that haunted yet freed him, as detailed in his book’s introduction.

ZEPHYR (born Andrew Witten) covered New York City subway trains with his signature lettering throughout the 70s and 80s graffiti heyday, he and his work appearing in iconic movies such as Wild Style and Style Wars among others. Dubbed “the elder statesman of graffiti” by the New York Times, ZEPHYR wrote under a variety of names in the early 70s, inspired by tags he encountered in places like the transverse roads below Central Park and on the backs of bus seats. He became ZEPHYR by the winter of 1977, when he left home at the age of16—a decision that haunted yet freed him, as detailed in his book’s introduction.

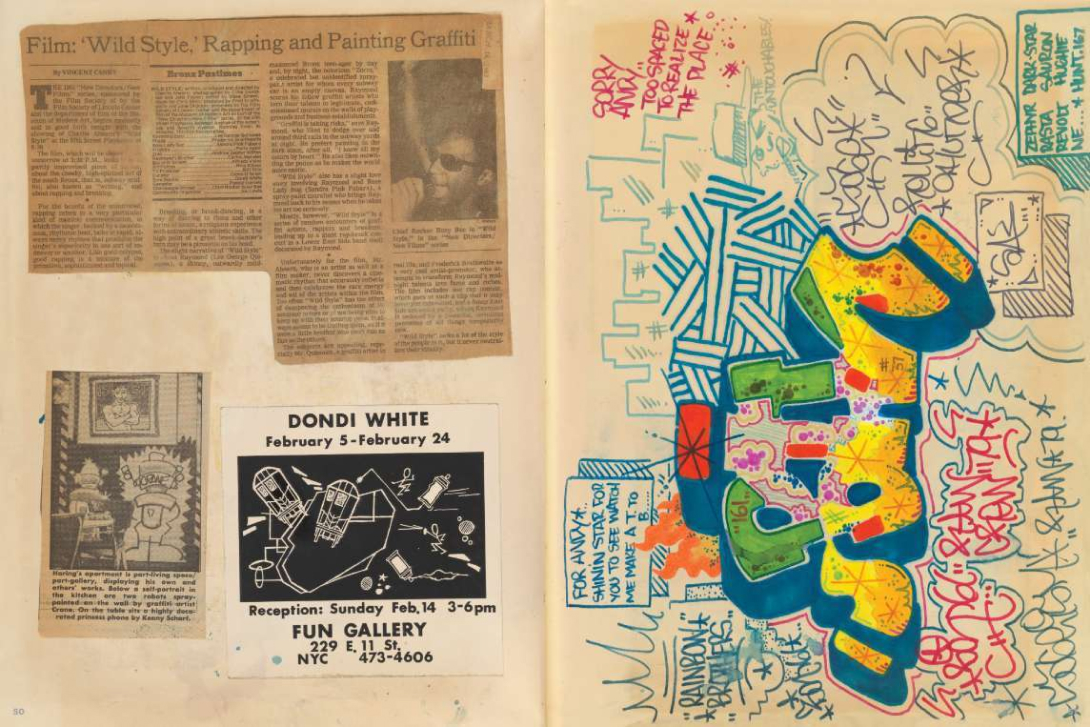

Part of the East Village gallery boom of the1980s, he has exhibited worldwide, alongside luminaries FUTURA2000, Kenny Scarf, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. ZEPHYR is the author of Stylemaster General, the biography of DONDI White.

What’s the biggest risk you’ve taken as an artist, and how did it affect your career or creative direction?

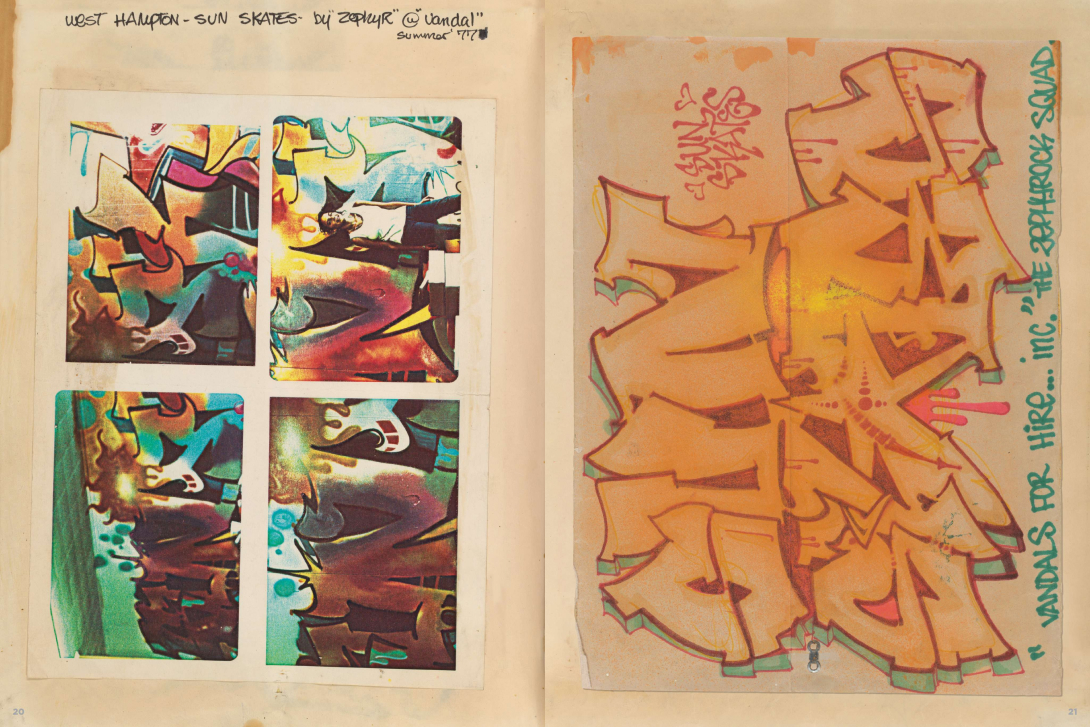

The simple answer is choosing to hitch my wagon to a group of artists called “The Soul Artists” in 1979. True story here. Straight out of High School I joined a group of renegade NYC artists called “The Soul Artists”. At the time, as an eighteen year old, I was already relatively ambitious and committed to an artist-for-hire future for myself. Years later I came to understand that I was actually a graphic artist in the making, but at the time I wasn’t even familiar with the term “graphic artist” or what that meant. I was raised on a steady diet of album covers from rock n’ roll records of the day—The Beatles and the Grateful Dead and whatnot. The graphics on them were what informed me as an artist, and I dreamed that one day I would create artwork for album covers too. I was very fortunate in that I was already drawing posters for smalltime local rock bands. The first time I ever realized that I could monetize my art was likely a painting on the back of someone’s jean jacket, and maybe I got paid ten dollars for it, so my beginnings as a so-called “professional artist” were very humble to say the least. That said, once I realized that people might actually pay money for my art, I was 100% determined to “make it”, whatever “making it” was to me in 1979. The story of the Soul Artists is the stuff of legend, particularly graffiti legend since we were all graffiti writers. Of all the things I could have done to develop my career as an artist, joining this group (fronted by the late Marc Edmonds, aka “ALI”) was arguably antithetical to anything “normal” or “responsible” or even vaguely “career-minded”, but I went headfirst into it with no regrets, then or now. I won’t go into great detail about the group and what transpired for the next two years, but just to get a flavor for it, we needed a place to make our art—specifically, at the time, to paint store signs for fifty dollars a pop (talk about humble)—so we took over, as squatters, an abandoned laundromat on the corner of Amsterdam Avenue and 109th Street in Manhattan. We fancied and promoted ourselves as a club or co-op of graffiti artists determined to transition ourselves into “legitimate artists”. It was an absolutely insane adventure and I like I said, I won’t bore you with the minutiae of it all—much has been written about the Soul Artists (and there is even a Wikipedia entry about ALI that is worth a read because he was a fascinating person)—but it was not the path I expected for myself after I graduated High School and it was, um, a “risky” choice to say the least.

If you could give one piece of advice to emerging artists, what would it be?

I can offer little to no advice, unfortunately, because I came up in such a different landscape than today. By way of observation though, many artists are brand-minded for themselves and for the work they seek. I can’t comment on whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing—because it’s neither. It’s just the order of the day. I’m from a time when the corporate footprint in fine art was light and vying for corporate attention hadn’t fully evolved yet. When I was writing art commentary in the 90’s I wrote a few pieces about what was then a developing intervention in which brands like Hugo Boss began subsidizing museum exhibits and it seemed like a scary thing to me. In my day, the 1980’s, the standout was Absolut Vodka, who seemed to collaborate with everyone and got a pass for sincerity. At one point a filmmaker tried to encourage me to criticize, on film, the love affair between many of my artist friends and large corporations like Nike and BMW. Not only was I not tactless enough to do so, but it would have been a blatant exercise in hypocrisy. I’ve done artwork for Sony and Virgin and others, and besides—why should I bemoan those options? If artists want to eat, they need to work. Of course the romantic revolutionary in me says that the artists are more powerful than the corporations, so knowing or courting their favor feeds the David and Goliath principle—but in reverse. As far as an artist as a brand, well that’s just the world we live in today, isn’t it? And since I’ve previously cited Coca-Cola’s advertising campaign as an inspiration for my own repetition and stylistic “brand” consistency [of my “ZEPHYR” graffiti] I’m in a glass house here, so I won’t throw stones.

How has your artistic style evolved over the years, and what influences have contributed to those changes?

I try to refrain from self-analysis in the “art department” so I’ll graciously pass on giving you a proper response. I will, however, go so far as to confess that I am a strong adherent to the Barry McGee school of thought. Specifically, I just like to doodle and nothing really gets beyond that. There was a time, after visiting Ron English when he was in Mark Kostabi’s employ, that I became horrified with my own inadequacies as a painter. I decided to try and remedy this by enrolling in a super-realist painting class taught by George Fernandez at the School of Visual Arts. Whatever outcome I was expecting, the bottom line was that I realized that I was an undisciplined scatterbrain and a bit of a slacker and that I should just accept it, and I did. As for the “early days” as an artist, for me, I wanted to be the second coming of the psychedelic artist Rick Griffin, and spent years trying, poorly, to mimic him. On one hand I look back thinking how pathetic that was, but on the other hand, his art still looks like pure God-sent gold to me, so there must be something in that. As far as presenting graffiti as “fine art” these days, I’ll put it this way: I prefer my diet vegan, but I try to serve my “graffiti art” up like meat and potatoes. In an increasingly “I was a graffiti artist, but now I’m special” environment, I try and provide an unadulterated sideshow.

What’s the most interesting thing about you that we wouldn’t learn from your work alone?

I can’t begin to guess what people might or might not find interesting, but some might find it strange that I have a collection of about sixty “vintage” racing bicycles from the 1970’s and 80’s. These machines, with their welded steel frames, are both aesthetically and mechanically beautiful to me. Generally, non-cycling enthusiast folks who have seen the collection just assume I’m nuts, which is a strong possibility.

In what ways has your cultural background or personal experiences influenced your artistic perspective?

Hmmmm…. That’s a great question and when I write the book I promise you are getting a free copy.